In a groundbreaking development that could reshape India’s public health strategy, a comprehensive study presented to the Union Health Minister has found that regular yoga practice may reduce the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes by as much as 40%. The report, titled Yoga and Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes – The Indian Prevention of Diabetes Study, was prepared by the Research Society for the Study of Diabetes in India (RSSDI) and formally submitted by Union Minister of Science and Technology Dr. Jitendra Singh on July 24, 2025.

This is the first large-scale, randomized control trial to evaluate the effectiveness of yoga as a preventive intervention in individuals with prediabetes. Conducted over a period of three years across multiple medical centers, including Delhi’s GTB Hospital, the study tracked nearly 1,000 high-risk individuals and compared the outcomes of those who practiced yoga daily with those who followed only standard lifestyle advice.

The results are striking: just 11.5% of individuals in the yoga group went on to develop Type 2 diabetes, compared to 18.9% in the control group. This amounts to a relative risk reduction of 39.2%, making yoga not only a promising low-cost solution but also more effective than some pharmaceutical interventions traditionally used for prevention. Past studies have shown that medications like metformin reduce diabetes risk by approximately 32%, while lifestyle interventions alone reduce risk by 28%.

Health Minister J. P. Nadda, who received the report, is said to be reviewing the findings for potential integration into India’s national diabetes prevention policy. With India already facing a massive diabetes burden — over 101 million diagnosed cases and more than 130 million people classified as prediabetic — the implications of these findings are both timely and urgent.

“This is a scientific milestone,” said Dr. Jitendra Singh, himself a noted diabetologist. “We now have robust clinical evidence showing that yoga, when integrated with lifestyle changes, can dramatically reduce the onset of diabetes. This could become a model for non-pharmacological interventions worldwide.”

The study employed a simple yet structured 40-minute daily yoga regimen, including basic asanas, pranayama (breathing exercises), and meditation techniques. Importantly, participants were trained in practices that could be done at home without the need for expensive equipment or ongoing supervision. Researchers noted that adherence rates remained high throughout the trial — a crucial factor in long-term lifestyle interventions.

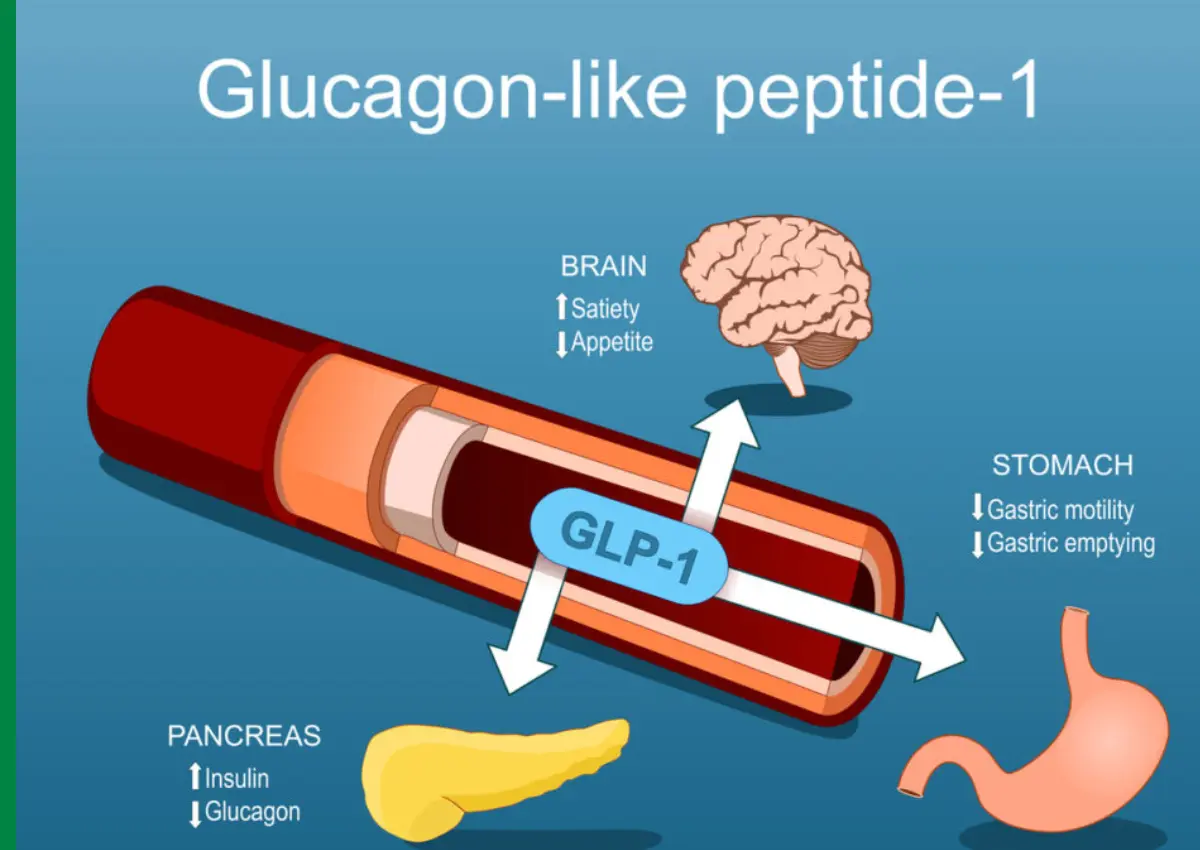

Lead investigator Prof. S. V. Madhu explained that the biological effects of yoga likely stem from a combination of improved insulin sensitivity, reduced cortisol (stress hormone) levels, enhanced metabolic regulation, and a calming effect on the autonomic nervous system. “Yoga works holistically. It improves both physical and psychological well-being, and this mind-body synergy appears to protect against the cascade of metabolic events that leads to diabetes,” he said.

The implications go far beyond clinical statistics. Diabetes is one of the most expensive chronic diseases to manage, placing enormous strain on both families and public healthcare systems. An accessible preventive approach like yoga — rooted in Indian tradition and requiring minimal infrastructure — could potentially save billions in healthcare costs annually. It could also improve the quality of life for millions by reducing their risk of diabetes-related complications such as kidney failure, blindness, and cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Singh has urged the Ministry of Health to integrate yoga into all major national health schemes, including the Ayushman Bharat initiative and the Fit India Movement. “We must act now to implement preventive models that are evidence-based and culturally relevant. Yoga offers both,” he said.

While yoga has long been promoted for its wellness benefits, the RSSDI study is among the first to offer rigorous scientific validation of its efficacy in disease prevention. It also sets the stage for further research. The study’s authors recommend that future work focus on replicating the results in larger and more diverse populations, standardizing the yoga protocols for clinical use, and integrating yoga-based approaches into school curriculums and workplace wellness programs.

The report has received enthusiastic responses from health experts, yoga practitioners, and public health policy makers alike. “This is exactly the kind of data-driven endorsement that is needed to move ancient practices into the mainstream of modern medicine,” said Dr. Meenakshi Bhatia, a senior endocrinologist at AIIMS. “Yoga is not a miracle, but this data proves that it can be a powerful medical tool — especially when used early and consistently.”

Dr. Randeep Guleria, former director of AIIMS and now an advisor to the National Diabetes Task Force, agreed: “This changes the conversation. We now have a cost-effective, scalable, and Indian-origin preventive model that can be taught in schools, community centers, and even via telemedicine.”

Public reception has also been strong. On social media, wellness experts and yoga gurus have lauded the government for finally bringing scientific rigor to traditional Indian knowledge systems. The Ministry of AYUSH is reportedly considering an expansion of its certified yoga training programs in light of the report’s findings.

The momentum could not be more needed. According to the International Diabetes Federation, India is projected to have over 150 million diabetes patients by 2045 if current trends continue. Many of these will be under the age of 50 — part of a younger, urban population increasingly plagued by sedentary lifestyles, poor diet, and chronic stress. These are precisely the issues yoga is uniquely suited to address.

As the government considers how best to translate this research into national policy, experts warn that implementation must be backed by adequate funding, community engagement, and sustained public education. Simply advising people to “do yoga” is not enough. Structured programs, certified instructors, and culturally tailored outreach will be essential for scale.

Still, the signs are hopeful. Dr. Singh has proposed launching a pilot program that would integrate yoga modules into existing public health screenings for prediabetes, with trained workers offering guided sessions and follow-up care in rural and urban clinics alike.

This is more than a wellness trend. It’s the beginning of a paradigm shift — one where India’s most ancient health practice could hold the key to solving one of its most modern public health crises.

If adopted nationally, yoga may not only transform India’s fight against diabetes, but also offer a globally replicable model for preventive care that blends tradition, accessibility, and scientific evidence.